1956: The Year Australia Welcomed the World

By Nick Richardson | Scribe | $35 | 336 pages

Why did Nick Richardson, adjunct professor of journalism at La Trobe University, with a doctorate in history and three decades in journalism under his belt, pick the year 1956 as the subject for a book? After all, as he puts it in his preface, “One of the hardiest clichés in Australian history is that the 1950s was a dull decade, when conformity settled on the nation’s shoulders, not to leave until the dynamic 1960s.”

From my perspective — having been a new arrival from the United States back around that time — this was no mere cliché. I was taken aback by just about everything here, and especially the weekends, when even the petrol stations were closed from noon on Saturday till Monday morning. “But what if you run out of petrol?” I asked my publican father-in-law, to which he blithely replied, “If you can’t see to it that you have enough of it on Saturday, you shouldn’t be driving a car.” I was stunned by the way people dressed, the women decked out in hats and gloves for a trip to the shops, and don’t get me started on the food.

But there’s always a but. I began to realise that under that cloak of dullness beat a heart of ferocious resistance. You would think that a girl who had just blown in from Hollywood wouldn’t have been shocked by the easy sexuality I saw, but I was. I had never even seen a bikini until I spent an afternoon on a Sydney beach. And my father-in-law’s pub was an education itself: it was called a hotel but no one outside the staff ever stayed there; the rooms were a fiction, designed to accommodate the licensing laws. As for the drinking, I’d never witnessed anything like it, or the hosing down of the walls after every session. By the time I arrived, the infamous “six o’clock swill” had been modified in New South Wales but not Victoria, which is where Richardson’s history is mainly set.

Nineteen fifty-six is his focus, but Richardson begins by taking us back to 1949, when Melbourne surprised everyone by winning the bid to host the ’56 Olympics. It was a terrific victory for Australia, a nation with sport coursing through its veins and a slew of athletes excelling on the postwar world stage (tennis players Lew Hoad and Ken Rosewall, and runner John Landy, to name just a few). At the same time, it was further away from the centre of the action than any previous host nation and, being in the southern hemisphere, meant that the majority of international participants would be competing in the wrong season.

In the six years following the successful bid, the organisers were beset with these and other maddening logistical problems. But underlying it all was Melbourne’s status as a provincial city in a young nation with a population of fewer than ten million and a dubious reputation bestowed by its racist immigration policy.

Richardson’s approach to his subject is both thematic and chronological. The resulting narrative is deftly woven and, surprisingly given all the detail, sweetly paced. Engaging too is the fascinating cast of characters, from the Soviet Pact participants and the spies keeping a watch on them, to the runners who carried the Olympic torch from Darwin and the photographer who took the shot of Ron Clarke using it to light the cauldron in the stadium.

Even those who come across as having been nightmares to deal with at the time make interesting reading. Take Wilfred Kent Hughes, an old-fashioned curmudgeon who ended up chairing the Victorian Olympic Committee almost against his will, or the foul-mouthed Avery Brundage, the United States representative on the International Olympic Committee, who never forgave the Australians for winning the bid, or let them forget what inept provincials they were when it came to putting on a show.

Then there’s Barry Humphries, whose Edna Everage had leapt onto the stage in 1956, and Ray Lawler’s Summer of the Seventeenth Doll. Yet arguably it’s Robert Menzies, Australia’s prime minister between 1949 and 1966, who strides above them all. Menzies, embroiled in the Suez Crisis, had little to do with the Olympics, and there on full display was his devotion to all things British, at a key moment of Britain’s humiliating decline as a world power.

In late July, in a sequence of events in some ways foreshadowing today’s contretemps with Iran over the Strait of Hormuz, Egypt’s president Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the Suez Canal, threatening British and French oil supplies. Nasser was implacable in the face of Western moves to undermine his control of the canal. A committee was formed with Menzies as its head, with the aim of persuading Nasser to come to his senses. He didn’t. Israel staged an attack, and the British and French swiftly joined in on the pretext of protecting Israel. But the United States felt the scheme had gone too far and refused its vital support. The British and French were defeated, with Menzies’s uncritical support for Britain having proved an undoubted failure.

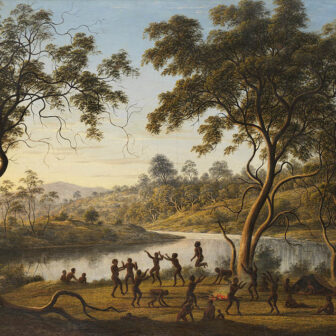

Richardson portrays the fifties as marking a significant transition. Australia was moving away from Britain and into the arms of America. Television’s arrival in time for the Games accelerated the process, but even before then Australian teens had been electrified by American rock and roll, and Sydney’s bodgies and their female counterparts, like the currency lads of the previous century, thumbed their noses at their super-starched elders and rebelled. For all that, they were as relentlessly sexist as the rest of society, a feature that Richardson deals with as well.

Britain’s hold on Australia may have been loosening but it was still strong. I was still in America when my Australian husband and I happened to pass a newsstand and saw the headlines about nuclear bombs being tested in Woomera. My husband pointed to them with pride and said, “See, we may be a little country, but have our own bombs.”

They weren’t Australia’s bombs, but the land they exploded on was, and it had been turned over to Britain without a qualm. Secretly, too. The government went through the motions of ensuring that none of the Indigenous people in the test areas would be harmed, and lied about that as well. Aside from the arrogance and racism, the problem was the breadth of the territory involved, and the insufficient resources allocated to protecting local people.

The same can be said of the difficulties encountered in preparing for the Olympics, with one cock-up after another arising from a curious lack of knowledge on the part of white city dwellers about the country they inhabited. On that score, it seems little has changed. Yet the Games were, on most accounts, a resounding success. Even their most vociferous critics at the time eventually allowed that, although some of the compliments seem backhanded. Richardson cites Red Smith, who covered the Games for US Sports Illustrated: “The Australian’s enthusiasm for sport is a consuming passion and it gives him high marks for intelligence. He is smart enough to prefer playing to working: he is jealous of his leisure and he makes use of it.”

Never mind the pronoun “he.” The fifties were openly sexist and racist, and few thought much about it then. But it was also a time when more Australians played sport than watched it, and the country prided itself on being “a workers’ paradise.” As we were sailing across the Pacific towards my new home, my husband told me that I would never see a “fat” person here and, believe it or not, it was true. From my perspective as an Australian today, it seems pretty clear the American influence has done a good job of changing all that, and quite a good deal more. •